The average client of the Christie’s auction house is likely unfamiliar with the concept of an Ether, the singular instance of the cryptocurrency Ethereum, or the artist Michael Winkelmann, better known as Beeple. Yet, in February 2021, a composite of the first 5,000 pieces of his art project Everydays sold at Christies for $69 million, or 42,329.453 Ether (now worth $115,849,363) {5/12/2021} [1]. This sale accelerated the public debate over non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and cryptocurrency to atmospheric heights. A non-fungible token is a digital token which authenticates itself using blockchain, the same technology that cryptocurrencies use to provide proof of ownership. Although anybody can screenshot and save these pieces of digital artwork to their hard-drive, the proof of ownership is tied to the 0’s and 1’s that code the digital token purchased in auction. Proponents of NFTs suggest that they empower artists to directly sell their digital art in the internet age, and celebrate it as a new collaboration between art and technology [2]. Critics argue a wide range of points, from the negative environmental impact of high computation costs in producing the blockchain authorization, to the breaking of established art traditions and techniques [3]. Winkelmann’s works can be seen as a form of collage, where he takes previously created 3D models and combines them into a cohesive artistic rendering using Cinema 4D, Octane Render, and Photoshop [4]. One work in particular, Into the Ether, simultaneously shows the distinct collage-like form of Winkelmann’s work while also taking a self-referential political stance on the sale of NFTs. Collage was first pioneered by George Braque and Pablo Picasso around the invention of synthetic cubism, where they incorporated physical elements into art using glue. It was a rejection of traditionally used Renaissance art materials, and allowed the artists to inject political overtones into the work, such as in the newspaper clippings of Picasso’s La bouteille de Suze. Michael Winkelmann’s 2020 work Into the Ether is a modern form of collage, displaying his views on the political discourse of the time and reflecting his production of art outside the traditional status quo of their era, both of which were also achieved by Pablo Picasso’s 1912 La Bouteille de Suze.

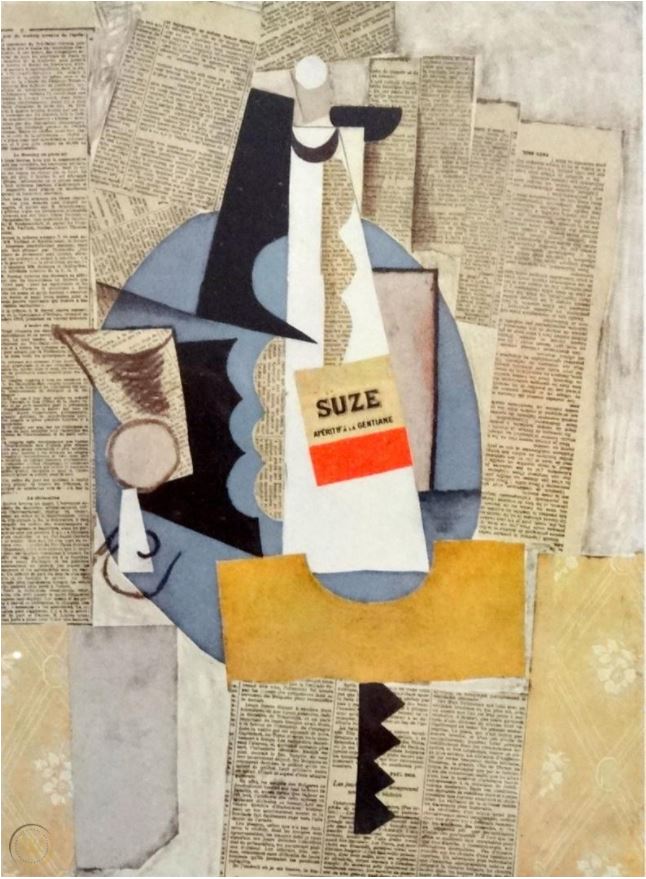

Before comparing the fundamental purpose of both works of art, it is important to first analyze the pieces in their own historical context. Picasso’s La Bouteille de Suze was made in 1912 after the start of the synthetic cubist movement. The year is significant, as it saw both the rise in French militarism as the country braced for the First Balkan War, as well as increased desertion and absenteeism within the army [5]. The work itself is a cubist inspired still life painting of a bottle of the French liquor Suze flanked on each side by newspaper clippings from November 1912, right after the start of the First Balkan War. There is a stark juxtaposition between the text of the newspapers on each side. The left side, placed upside-down, discusses brutal descriptions of the war along with nationalist reports of military advances by Serbian troops. In comparison, the right side of the newspaper, correctly orientated, portrays general leftist positions on the political discourse of the war. The subject matter of the still life plays an equally crucial role, where the table, bottle, and glass all set us concretely in the setting of a working class café. These proletariat cafés served as a location of political argument and general anarchist discussion. Lastly, original reproductions suggest that the label of the bottle was red, giving the three colors present in this piece the important symbolism of reflecting the tricolor flag of the French republic [5].

Winkelmann’s piece, Into the Ether, is a piece of digital art created towards the end of 2020, a year that has been marked by a number of turbulent events. To name a few: the global pandemic and the resulting national recession, the U.S election, the George Floyd protests, Black Lives Matter movement, and the feverish rise of cryptocurrency. Although much of Winkelmann’s other works draw inspiration from these political discourses, Into the Ether is squarely situated in the debates over cryptocurrency, and non-fungible tokens in particular. The work displays a large purple crystal, in the shape of the logo of Ethereum, the second largest cryptocurrency by market capitalization [6]. Two explorers suited for space exploration look upon the crystal in awe, with the rightmost explorer reaching up to touch the crystal. Printed on the left explorer’s tank is the acronym HODL, standing for “Hold on for dear life,” a popular phrase associated with cryptocurrency investing. The phrase is employed to recommend investors hold their stakes for as long as possible, implying that today’s meteoric rise seen in cryptocurrency is only the beginning [7]. The overall location of the piece appears to be some extraterrestrial planet judging from the rocky environment, hazy atmosphere, and suits the explorers don, suggesting that Ethereum is otherworldly in nature. This work itself, like most of Winkelmann’s works, was created using a suite of 3D rendering tools. Winkelmann will select 3D models from a curated collection of assets developed over his past 12 years working in Cinema 4D, directly inserting them into a blank space. Assets will then be textured and colored, and additional effects are added in Photoshop, such as the light emanating from the Ethereum crystal. Background effects, like the atmospheric sunset texture in this piece, are applied in photoshop along with final color grading techniques [8]. Approximately 201 copies of Into the Ether were minted as NFTs, and sold for $969 a piece [4]. Most recently, a resale of this work went for 140 ETH, or around $383,159 at the time of writing [9]. With these analyses of the works in mind, we’ll reflect on the reactions to these techniques.

Cubism itself was initially looked down upon by the established art world. In Daniel Kahnweiler’s Rise of Cubism, he asserts, “Cubism was a derogatory term applied by its enemies. [10]” In this case that enemy was an art critic from the Gil Blas, Louis Vauxcellers [10]. The shift from analytic to synthetic cubism was met with the same opposition of the avant-garde, in this case a negative reaction to the techniques of collage. Antliff and Leighten suggest, “collage problematized the presence of the hand of the artist by shifting the ‘master’s touch’ from the profoundly mystified act of painting to cutting, placing, and gluing, with drawing often used not to inspire admiration of its facility or elegance… [5]” Essentially, collage was an intentional abandonment from oil paints that represented traditional art [11]. Although Winkelmann’s collage does not take the form of glued papers onto canvas, the foundational elements are similar. Winkelmann produces one of these works of art every single day, so it’s extremely likely that both the figures in Into the Ether are originally the same 3D asset, which has been colored and articulated by the artist to provide some differences. It’s even more obvious in other works by Winkelmann where 3D assets are repeated without being modified. This is quite similar to how Picasso cut and glued newspaper trimmings into his La Bouteille de Suze. Winkelmann also cuts and “glues” pictures into his scenes, such as the cut photograph of a sunset which has been pasted into the background behind the Ethereum crystal. In Winkelmann’s case, the use of collage is not as apparent because the background is deliberately blended into the color composition of the scene. Despite this, Winkelmann’s 3D modeling can be readily compared to the historical development of collage both in technique and social reaction.

Digital art as a medium is similar to collage in its position outside of the traditional art world. Debate is still popular over whether digital art should be considered “real art” [12]. Digital art was not sold by traditional fine art auction houses, a norm subverted with the historic sale of Winkelmann’s NFT at Christies [1]. Digital art is not yet widely accepted in mainstream galleries or museums. However, it is just as popular if not more popular than traditional art. Digital artists rank high on social media often garnering thousands of followers. Winkelmann himself has 2.1 million Instagram followers as of this writing [13]. Even inside the digital art world, Winkelmann’s work stands out. Some digital art attempts to recreate the brush strokes and elements of traditional painting, but Winkelmann’s craft involves a relatively small amount of those elements. The 3D modeling and asset creation in his work straddles the border between digital art and engineering work. Additionally, the sale of his work as NFTs results in greater scrutiny due to their negative environmental impact and complex economic dynamics. In today’s art world, both collage and digital works are strongly associated with our perceived notion of art. However, like collage, digital art acts as a strong divergence from traditional Renaissance art, and faced initial criticism and debate [14].

As another point of comparison, both Picasso and Winkelmann knew when creating these pieces that the work was expressive of their political viewpoints. Leighten argues that French life was “saturated in a politicized rhetoric that insisted in the ideological implications of everything, especially art, and above all a self-consciously rebellious avant-garde art [5].” When Picasso was later asked by the journalist Pierre Daix, Piacsso stated that La Bouteille de Suze utilized newspaper clippings for the express purpose of showing he was against the Balkan conflict [5]. From these two points, along with the previous analysis of the piece, it’s quite clear that La Bouteille de Suze was created as Picasso’s addition to the political discourse surrounding the events of 1912. This political message is of course added on top of the fact that synthetic cubism and avant-gardism was essentially leftist in nature, supporting left wing stances by diverting from traditional techniques and subject matter. The contrast between the sides of the newspaper serves to highlight and frame the art in the debate between French Nationalists and anti-war leftists. The still life subject matter displays the seditious conversations that occurred throughout Paris in proletarian cafés. The symbolism of the French flag reminds the viewer of the slogan of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, ideas that Picasso thought contrasted with the government’s wartime policies [5]. Across the board, the leftist political message of this work is evidently clear.

Into the Ether works in a similar vein by acting as a critique of cryptocurrency and the neoliberal ideologies that prominent cryptocurrency investors push. We know that Winkelman’s works are politically charged in nature, he even states that he watches both CNN and Fox news at the same time on two opposing monitors while he works [1]. Additionally, a large number of Winkelmann’s works explore the theme of technological post-capitalist dystopias. Many of his works tie these concepts into cryptocurrency, including Illestrater, Bull Run, Post-Capitalism, Cryptocurrency is Bullshit, and of course Into the Ether [15]. The work is clearly meant to poke fun at investors who are absolutely enamored with cryptocurrency. The figures in the work look upon the Ethereum crystal with wonderment, and one could argue that the right figure is displaying an investor’s greed with his right hand reaching up to touch it. The crystal itself appears godly, floating in the air with a spread of illuminating rays and a slight rainbow glow on the right. Lastly, the HODL acronym on the tank of the left figure serves two purposes. It is an attempt to highlight a phrase that is often parroted by cryptocurrency investors on social media, and used to satirize them by opponents of cryptocurrency [7]. Additionally, HODL became a rallying call of retail investors funding Gamestop and Dogecoin (another cryptocurrency) during their recent spikes in value, much to the chagrin of institutional investors and large investment firms [16]. Thus, it also emphasizes the anti-traditional sentiment of this piece produced through its role as digital collage and it’s sale as an NFT. In the context of his other works, it appears that Winkelmann is worried that cryptocurrencies, NFTs, and the free market ideals that come with them could very well be a slippery slope into a dystopian future.

Yet, despite its role as a satirical and antagonist piece against cryptocurrency, Winkelmann’s relationship with the subject matter is more complicated than Picasso’s anti-war beliefs. Winkelmann is now the third richest living artist in the world due to his involvement in the cryptocurrency market, which NFTs are inherently part of [1]. Although he makes fun of cryptocurrency obsessed investors, he does support the role of NFTs and their potential as another means for artists to interact directly with the buyer, suggesting it is an “interesting and exciting space,” and that “every 3D artist will know about cryptoart within three to six months. [2]” Winkelmann’s legacy is now fundamentally tied to the success of NFTs; as they continue to gain popularity he will be considered both a pioneer by NFT fans and a harbinger of change by more traditional artists, gallery owners, curators, and auction houses alike. Whatever the future of NFTs and cryptocurrency holds, it is certain that the traditional art market will need to adapt to this new form of digital art production, sale, and collection [17]. Overall, we can draw a neat comparison between the two works of art displayed here. Into the Ether shows how both Michael Winkelmann’s role in NFTs and the use of 3D rendering as a form of collage emphasize the political ideology of this work’s subject matter. Similarly, Pablo Picasso’s collage techniques framed against the cubist subject matter enhance his deeply political anti-war themology.